Tycho Brahe and Giovanni Battista Riccioli, left to right (image credit: Wikimedia Commons)

As ideas about motion began to change, new methods were devised to detect the Earth's rotation (if it had any). Natural philosophers began to realize that an object already in motion would continue its motion even if nothing pushed or pulled it. For example, an arrow fired from a bow will keep travelling long after it has left the bowstring. The Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe, the Italian astronomer Giovanni Battista Riccioli, and the French mathematician Claude Dechales realized that the sustained motion of an already moving object meant that objects should move differently on a rotating Earth than they do on a stationary Earth. Cannonballs should follow curved rather than straight paths, and a ball dropped from a high tower should actually land very slightly to the east of the tower's base rather than far to the west as Aristotle had argued. Based on reports from artillery experts and other data, these men were convinced that these deviations did not occur and therefore that the Earth must not rotate. (We now know that the deviations DO occur, but they are too small to have been measured at that time.)

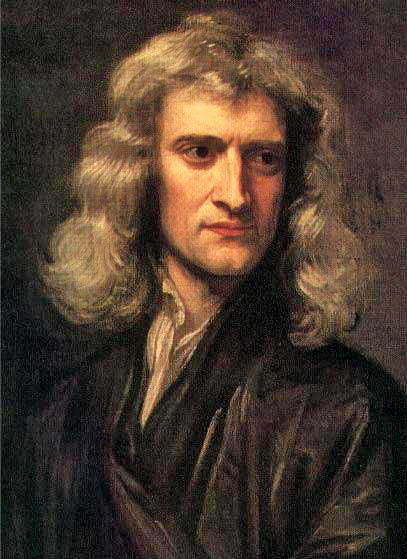

Issac Newton (below), who refined and improved these new ideas about motion, wrote to Robert Hooke in 1679 to suggest an experiment to demonstrate Earth's rotation. By this time the idea of a rotating Earth had become widely accepted, largely because of the success of other parts of Copernicus' theory (the orbit of Earth around the Sun), but the Earth's rotation had not yet been demonstrated. Like Riccioli and Dechales, Newton predicted that a falling object would fall slightly to the east and he suggested a method for measuring this deflection. Hooke claimed to have performed the experiment and detected the eastward deflection, as well as a slight southward deflection, but Hooke's measurement errors were so large that his results were not taken seriously. Others repeated Hooke's attempt to measure the eastward deflection and reported some success, but the deflection was so small and the measurement so difficult to make that these experiments did not serve as a convincing demonstration of Earth's rotation.

More convincing evidence for a rotating Earth came from the Earth's shape. In his monumental Principia of 1687 Newton showed that a rotating Earth should not be perfectly spherical, but instead should be squished along the poles and bulging out at the equator. Such a shape is known as an "oblate spheroid." French astronomers and surveyors traveled to what is now Finland and Ecuador in order to make measurements that would reveal deviations from a spherical shape, and their results convincingly showed that the Earth was oblate just as Newton predicted. This as evidence for Earth's rotation, but it was very indirect. By the mid-19th century, even though the Earth's rotation was fully accepted, there was still no direct and convincing way to demonstrate that the Earth spins.